When humanitarian emergencies strike, these volunteers are ready to share their geospatial skills and help communities map their way out of crisis. You, too, can lend a hand.

After Cyclone Idai made landfall in Mozambique in the middle of March 2019, it left behind more than 1,000 casualties, miles of damaged roads, and ruined at least half of that year’s annual crop harvest. The port city of Beira, in the eastern part of the country, was the hardest hit, whipped by winds that reached 106 miles per hour and torrential rain that caused widespread flooding.

Christopher Jarvis, along with other international humanitarian workers, soon arrived at Beira’s airport to support the rescue efforts in the country. Partially damaged by the storm, the airport was reopened and functioned as an operations hub for various disaster response activities.

“When we landed it was intense from the start,” says Jarvis. “There were loads of people rushing around and working from the small airport.”

Jarvis is a volunteer at MapAction, a UK-based non-profit organization that provides geospatial, mapping, and data know-how to help its partners anticipate, prepare for, and respond to humanitarian emergencies. The organization has worked in more than 140 humanitarian emergencies in 80 countries.

“MapAction was founded in the early 2000s when mapping went digital to support decision-making in humanitarian response,” says Alex Macbeth, the organization’s head of communications. “It was started by several people with the insight and vision to realize what a transformative difference rapidly created situation maps could make in humanitarian emergencies.”

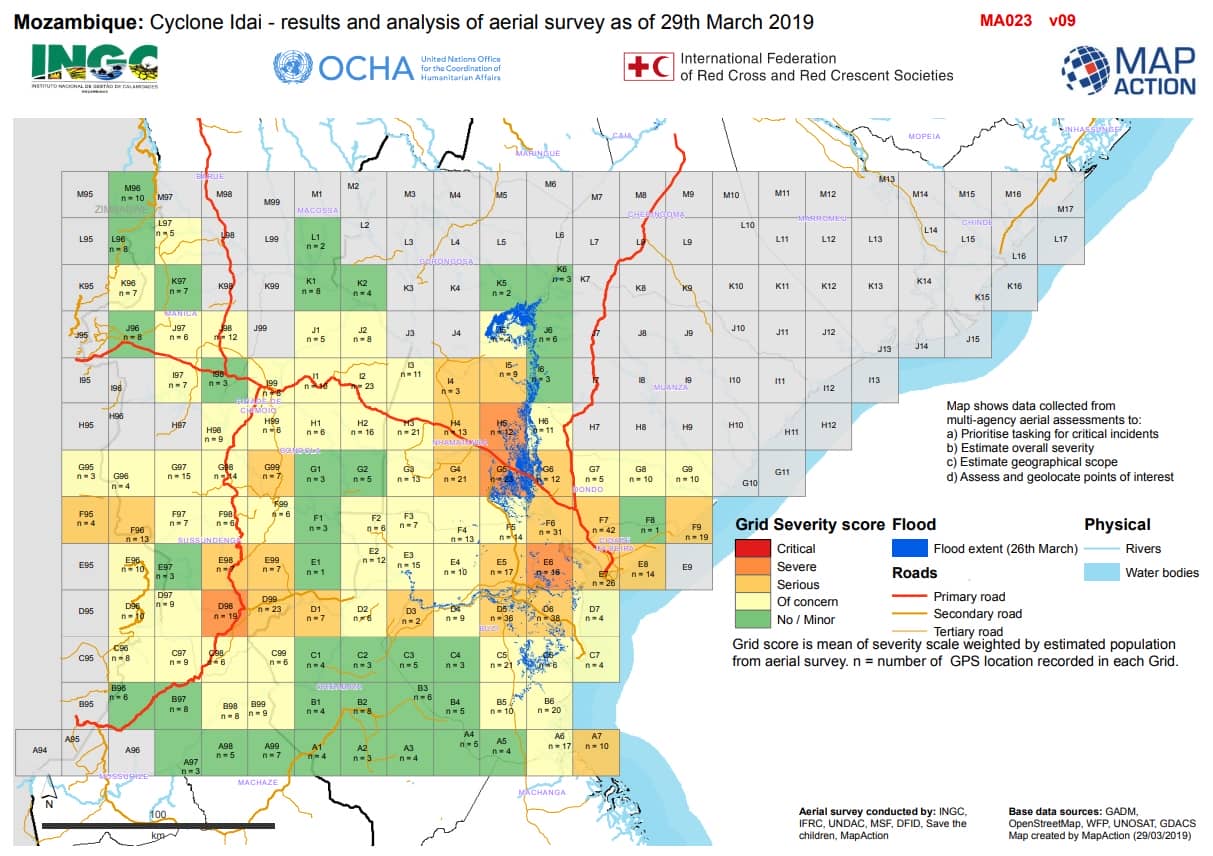

Flood severity map created by MapAction Mozambique in support of the humanitarian response to Cyclone Idai, 2019.

One of MapAction’s primary roles is to create maps that can support operations during crisis situations. Their work is especially indispensable in locations where maps are either hard to compile or are missing, as in the case of many developing countries. Humanitarian workers need maps not only to show the location of the crisis but also to monitor how events evolve in order to best help impacted communities. As such, mapping is often the first step in any emergency response.

In the aftermath of Idai in Mozambique, for example, immediately locating the flooded communities was critical. But doing that required mapping the extent of the deluge, a challenging task that Jarvis had to do before anything else.

“The floods were huge, and it was really difficult to figure out how big the scale was,” recalls Jarvis of his first deployment with MapAction. “We knew it was big and it was bad, but we didn’t know how big and how bad.”

So, with mobile phones at hand, Jarvis went up in a helicopter to conduct aerial surveys together with the Red Cross and the UN. Within three days, he was able to observe from the sky an area of around 16,000 square kilometers. This allowed him to create a map of the affected areas and identify which places needed help straight away.

Christopher Jarvis working on maps of the flood disaster in Libya.

“I produced the aerial survey map, which we updated twice a day for five days,” says Jarvis. “There is only so much you can do to help with the resources that you have, and when it’s such a massive area you need to focus the help so it can maximize the humanitarian benefit of the people affected.”

According to Macbeth, maps are key to search-and-rescue operations because it is crucial to know where to send rescue personnel and to identify areas which have been searched and which haven’t. Other maps can help plot a path for emergency aid to those who need it most using the fastest and most accessible routes. “Each map is created to help decision-makers act more quickly and accurately,” he says.

Darren Connaghan, another volunteer with Jarvis in Mozambique, remembers his own initial volunteering deployment with MapAction. In 2005, he was sent to Pakistan for three months after strong tremors devastated the northern region of the country.

“The earthquake was one of the biggest in Pakistan for many years, and the international response was still ongoing months after the event,” he says. “I was available at that time, so I flew out and joined the UN team.”

The 7.6 magnitude earthquake that struck the Kashmir region in the Himalayas destroyed 3 million homes and left 75,000 casualties. Urgent humanitarian assistance was indispensable in this mountainous area, especially as the cold season was approaching and heavy snowfall could block many roads disrupting humanitarian logistics.

Cyclone Idai left a trail of destruction through Beira City in Mozambique.

“Winter was about to start, so it was vital to understand how temperature and snowfall can affect the way resources can reach those who are affected in order to keep them alive during the cold period,” says Connaghan. “Maps and information management were required to make sense of the spatial destruction, the number and location of people in need, and what that need would be.”

MapAction’s cartographic efforts in Pakistan supported the work of other humanitarian organizations which were aiding affected villages. It was also significant for the organization because the way it currently creates and organizes its mapping projects were mainly developed from their experience in that country.

“Many of the structures that MapAction uses now were developed over time in Pakistan,” says Connaghan, who has been volunteering with MapAction for 18 years. “These include our map template design, the directory structure for storing all the data we use, the symbology, and the naming.”

But before MapAction volunteers can create maps, they must collect, assess, and organize the data that they need. Doing all this is often not straightforward as they typically use open source and publicly available datasets.

“We can only work with the data available,” says Macbeth. “In some territories, the quality of data limits our work.”

Gathering data to create maps during humanitarian emergencies can also be overwhelming. Jarvis says one can have too much information sometimes and then not have enough during other times.

“You get flooded with reports and documents, rumours about different figures and what’s going on in different places, and confusion from people who have just arrived in a country that they’ve never been in,” he says. “But at the same time, you almost never have good data on who is affected, or the administrative boundaries that are found online are not anywhere near the same as the current boundaries or places that people know.”

That was what happened in Mozambique when the map data obtained by MapAction was not the one recognized by the national government.

“One of the tasks whenever a response is required is to do a data scramble to source as much base data as possible,” says Connaghan. But using an unofficial baseline map posed a big problem for the team. “A lot of data was being collected against the administrative areas that we had no knowledge of.”

In order to deal with that kind of challenge means communicating with as many decision makers and data providers as possible, Connaghan says. “Many of the products we produce are incomplete, but when distributed to the responding agencies who have not provided the information, we usually garner a response,” he says. “Data generally flows in quite quickly after that.”

Once data and data sources have been ironed out, creating maps usually turns out to be like any other GIS project. For example, the team chooses between using either commercial or freeware mapping software, swapping one for the other depending on their needs.

“We have been fortunate that ESRI has been a massive supporter of MapAction, almost from day one. They provide multiple licences for MapAction to use for their ArcGIS software,” says Connaghan. For their deployable laptops, QGIS open-source software is used, particularly during training and capacity building activities in places that cannot afford the cost of ESRI licences. “We provide templates and symbology to them in QGIS,” he adds.

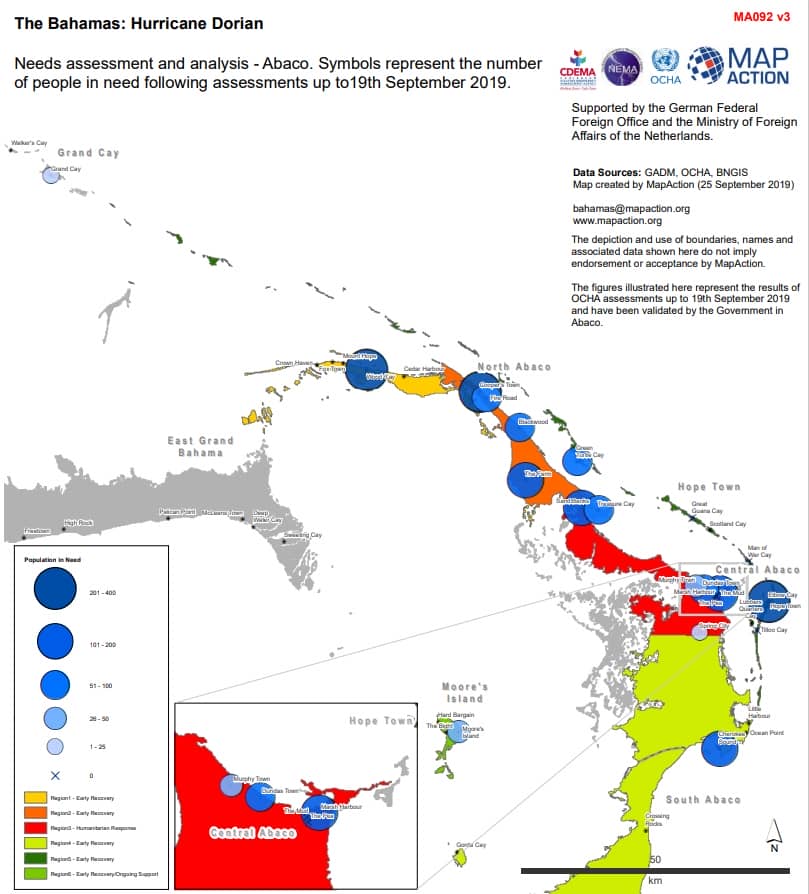

Population map of people in need of aid in the aftermath of the Hurricane Dorian in the Bahamas, 2019.

Such flexibility does not only apply in their ability to use different mapping platforms to accomplish their work. Volunteers must also be ready to adapt to changes in deployment locations at a drop of a hat. Volunteer Alice Goudie, for instance, was preparing to go to Bolivia to help map forest fires in that country. But she soon found herself boarding a plane to another destination.

“My first emergency deployment was to the Bahamas for Hurricane Dorian in 2019,” says Goudie. “I’d just finished all my MapAction training and was due to go to Bolivia, but the situation changed and suddenly I was on the plane to Nassau.”

Hurricane Dorian, one of the strongest storms to ever hit the region, had stalled for 40 hours causing damage to more than 75 percent of all houses along its path. “As the Hurricane was moving so slowly, it was really hard for people to quantify how bad the damage was and which areas were most badly affected,” recalls Goudie. “Lots of people were arriving on the ground with little understanding of the situation and going to devastated areas with limited communications, so maps were the best way of explaining what was going on and where aid was needed most.”

Goudie, who works as an analyst for a geospatial software company, first got involved with MapAction after listening to a talk while she was doing her graduate studies. “I wanted to be able to use my skills for something worthwhile, and they sounded like an amazing organization. Also, they said we needed to be happy camping in tough environments and going for days without a shower, which sounded right up my street.”

During her deployment in the Bahamas, she learned that time is of the essence especially to get a map done promptly to enable someone to go into the field and make decisions.

“The maps we create do actually make a huge difference, and sometimes things that we think are very simple can be critical for making sure that the right aid gets to the right people in the right place and at the right time,” she says. And after having been on five emergency missions with MapAction since 2018, Goudie looks forward to more deployments. “I have much more to learn and many more assignments to go to.”

Goudie, Jarvis, and Connaghan are part of the more than 70 volunteers at MapAction. As of this writing, the three volunteers have been working on maps to support the humanitarian efforts in Libya after a massive flood swept the town of Derna. When a disaster like that happens, the UN or any regional partner can request MapAction to help in mapping the situation. “We then put out an alert among our whole team to see who is available to deploy or to support remotely,” says Macbeth.

And how does one become a MapAction volunteer? Macbeth says MapAction is looking for enthusiastic professionals who have a desire to commit to a great team and to help MapAction make a difference. And while it helps to have mapping skills, a knack to do other duties is also sought after.

“We need project managers, software developers, data engineers, data visualization specialists, communications specialists, and more,” he says. “People fluent in second languages other than English are particularly welcome.”

Jarvis, who works as a senior scientist in the UK Public Health Agency, adds that people with leadership and communication skills are also needed. Folks who can be calm in intense situations and have the ability to think clearly while weeding through all the information in order to determine what is important can be an asset to MapAction’s work.

In order to help them prepare for work on the ground, MapAction volunteers receive training year-round. “Training allows the MapAction volunteers to form a working team really quickly and just crack on with what needs to be done,” says Jarvis. He is now part of MapAction’s board of directors and has been on 12 missions since 2019. “I don’t see that stopping anytime soon.”

Connaghan has the same sentiment, even after almost two decades of volunteer mapmaking. He still has the passion and desire to provide support either in the field or remotely.

“My day job is challenging, but a MapAction deployment requires control, chaos management, calmness, and confidence in your decision making,” he says. “We are respected within the UN and humanitarian environment.”

For Goudie, MapAction is a fantastic organization to volunteer with. “It requires a very unique set of skills, but if you have them then it is an amazing way to do something meaningful,” she says. “You can use your skills in a way that makes a real impact and see parts of the world that most people don’t get to go to.”

To be able to create maps while working in difficult situations, however, requires GIS skills accompanied with grit and compassion.

“There are a lot of people with data and GIS skills, and also lots who can rough it in harsh environments, but not many have the one and the other,” says Jarvis. “So, if you have both together, then you should really think about how you can use that combination to help others.”

You Can Help

Without adequate funding to work on emergency response, MapAction cannot respond to as many disasters as it would like. By supporting MapAction now, donors will make a real difference to communities working hard to improve their own disaster resilience. If you’d like to support MapAction’s work contact [email protected].